THE SYLLABUS: We Can Dismantle the Master’s House by Reforming the Master’s Tools

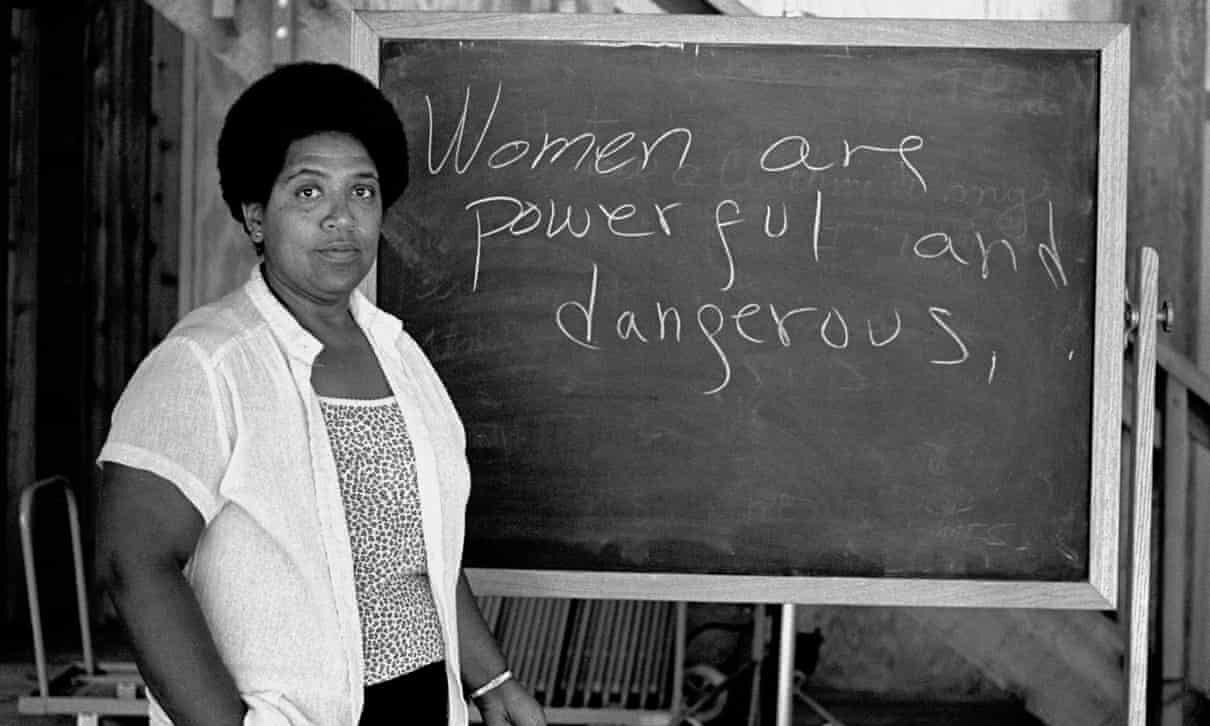

In 1984, the self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” wrote an enduring essay titled, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” in the book of essays titled Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. The essay, about the intentional oversight by academia, of Black, indigenous and brown women and women of LGBTQ communities, assailed the continuing efforts of the academy and other major social institutions, to erase the experiences of these communities of women, mostly for the maintenance of a mode of learning rooted in white supremacist thought. Over the years, the title of her essay has become a rallying cry for activists advocating for institutional change for the health, safety and inclusion of people who have been marginalized. The declaration, by many people who have read her work since it was first published, insists that the essay calls for tearing down existing structures, built upon a predatory capitalist ideology (and that permeates all systems), should be torn down and we should start all over again with something new.

However, a close reading of Ms. Lorde’s essay, and her body of work, reveals something different than the cursory reading that has come to define this particular piece of work. What the essay does is declare that people who have been disregarded, take back what predatory capitalism*, and all of its systems, has stolen from us. It is a call to reframe, reshape and reuse the tools that have been used to subordinate generations of people.

I begin my series posts by discussing this foundational work because part of the mission of Erie’s Black Wall Street is the support of Black people via the tools of capitalistic gain. This might seem nonsensical. After all, the only reason that the population of Black people in the United States is at its current size is because law and policy makers used capitalism to justify the kidnapping and lifelong enslavement of our African ancestors. It seems a dangerous system upon which to rely.

However, we lay the foundation of our mission upon two of the primary characteristics of Black people in this country – community and collective identity.

Let’s start with community.

I’ve lived in many states in this country from Los Angeles, California to Rochester, New York and many in between. A consistent factor in all of my moves and travels is that wherever my family, or I alone, went, even if we knew no one else, we were welcomed members of The Black Community. Though no ethnic community is monolithic, our family’s inclusion within each Black community was never questioned. We were lovingly received. This is, in part, a direct response to the historical cultural rejection of Black people by white communities.

The second major characteristic is collective identity.

As a graduate of an HBCU I learned, as a very young adult, that no matter the type of community from which we came, no matter the lightness or darkness of our skin, no matter our socio-economic background, no matter our hobbies, no matter our family structure, we all identified as Black, and as such, members of The Black Community. These two factors form the foundation of the other communities of which we all, eventually, became a part after we graduated.

In many ways, HBCU’s are prime examples of the message of Ms. Lorde’s piece. Higher education in this country is “the master’s tool.” It has traditionally been used to teach skills, and a particular knowledge set that omits, almost entirely, the work and necessary contributions of people of color to the body politic of the United States. In the case of education, The Black Community, used the tool, reformed it and then used it to include a breadth and depth of knowledge that many predominantly white institutions fail to reach, by design. The Thurgood Marshall College Fund indicates that 40% of Black doctors, 50% of Black engineers, 50% of Black lawyers and 80% of Black judges are graduates of HBCU’s. This is a case of taking what has been stolen from us and shaping it for our own success in systems that are not necessarily built to include us - precisely Ms. Lorde’s point.

Erie’s Black Wall Street has a similar strategy. By design and definition, and in its broader sense in the U.S., capitalism is predatory. At the country’s inception, it was used to justify indigenous genocide, steal land from Mexican people, enslave African people, exploit the labor of people immigrating to the country and to maintain the subordinate status of women, yet, within each of those communities, it has also been used as a catalyst for communal support, uplift and aid to its members in the variety of way that they quest to achieve. The goals of EBWS are to identify, support and provide ways for our community to succeed in a capitalist economy, using the concepts of cooperative economics. (Pay attention to that phrase, you will see it a lot in the weeks to come.)

We, at Erie’s Black Wall Street, understand the message of Ms. Lorde’s declaration. The tools that we will use to support the entrepreneurship of Erie’s Black community are rooted in the collectivist identity of our culture in the United States while, at the same time, utilizing the more positive, uniquely American, ideals of capitalist enterprise for uplift. We will also turn an eye toward the positive development of Erie’s broader community, because the very concept of the collective means that when one community succeeds, all communities thrive.

-Dr. Rhonda Matthews

*”Predatory capitalism refers to cultural acceptance of domination and exploitation as normal economic practice.”

Source: https://tinyurl.com/ybvxxrjo

Next week: The Black American Experience and Cooperative Economics

Audre Lorde, Author of Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches.